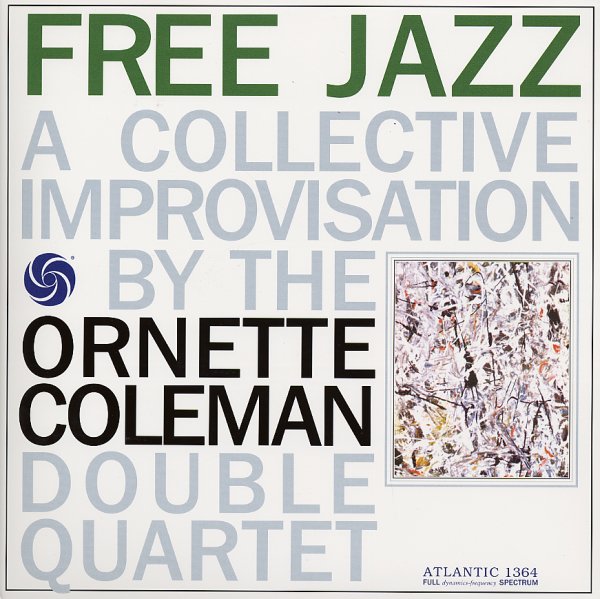

Atlantic; December 21, 1960

http://www.ornettecoleman.com/

Alright, I'm going to come out and say it right now: Free jazz is some of the hardest shit to write reviews for. I'm not trained in music theory, and I'm sure a lot of the techniques and nuances probably sail right over my head. Shit, most of the musicians who are playing the stuff are often feeling it out to some extent as they go. What hope do I, some dumbass amateur columnist, have in accurately capturing one of the most controversial watersheds of post-bop jazz in my typical avalanche of hyperbole, redundant verbiage and four-letter words?

No fucking idea. But I've decided that it's important you know this album. So on I go.

At the time of Free Jazz's release, alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman was pushing the jazz form, already expanded by ten years of bop and "cool," right to its ragged edge. 1959's somewhat boastfully titled (but for good reason) The Shape of Jazz To Come, even in an era of Monk, Mingus and Taylor, was pretty far "out." Sure it was (mostly) pretty harmonious, and it was mostly in blues scales, but by throwing out chordal structure in general and the piano altogether, it was a fairly radical release at the time. Although some argued that this album would be the downfall of jazz into realms of skronky noise, most listeners today would find the work of the quartet (Coleman, Don Cherry on cornet, Billy Higgens on drums, Charlie Haden on double bass) beautiful and shapely listening that's aged very well after fifty years of relentless musical advances.

Not satisfied with this classic, in 1960 Coleman showed the world he wasn't fucking around and rounded up his next ensemble of musicians; see above, but add another quartet--Eric Dolphy on bass clarinet, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Scott LaFaro on bass, and Ed Blackwell on drums. Now if you know anything about jazz, those are some impressive names. Dolphy in particular might be my favorite reedist (I think that's a word) in the whole genre. The session was recorded in stereo with one quartet in each channel, a pretty interesting use of then-novel technology.

Anyway, now that I've bored you with the technical details: Free Jazz is where the controversy really starts. To this day, there are plenty of listeners and conservative music critics that still think this album sounds like a bunch of car alarms going off. They are wrong.

Sure, this nearly 40-minute session (it's the only track on the album, unless you count the bonus 17-minute rehearsal) starts out somewhat frenzied, with a big burst of reeds and brass going every which way but then Ornette's plastic sax, Cherry's horn and Eric Dolphy's bass clarinet acquire a clear focus, state an elegant melody, and split off again. A number of similar, short fanfares are introduced and elaborated on throughout, with Ornette trading wry lines with Dolphy's cheeky clarinet, Hubbard's deep trumpet and Cherry's rounder sound. There are no clear solos, per se--while there is space for them, the other musicians are free to "comment" at any point. The double rhythm section whips up a complex uptempo pulse, with one drummer playing "straight" and the other playing in double time. The overall effect is like that of a conversation at a lively party where long streams of amiable dialogue from the individual voices are interrupted by a "laugh" or a lengthy aside from another voice, while bass and drums form the sounds of a crowded, busy room. There is a natural give and take and rhythm to this piece, and despite the "free" moniker it's not chaotic in the least.

Around the 25-minute mark, the blowing trails off leaving some space for the two bassists to chew on, and the two drummers continuing their steady shuffle. This is one of my favorite parts of the gig, as Haden (who has the deeper sound of the duo) is a BEAST on his upright and LaFaro is no slouch either. Then the whole band comes in with a big burst around 29:50, and fades into the background to let the basses continue their back and forth. The album concludes with a few more blowouts and the two drummers cutting loose with some excellent soloing, trading blows like a couple of prize fighters. Magnificent.

After listening to this album, it's clear that while Coleman is no doubt an innovator (the dude's still around; his 2006 live recording Sound Grammar won a Pulitzer for Music), the man's roots are still in classic bop players like Hawkins and Parker, never truly rejecting melody or structure (hence the rehearsal) while retaining the improvisational fire and groundbreaking spirit that characterizes the free jazz artist. He was sometimes panned and misunderstood (he was even attacked and had his sax destroyed by some asshole at an early gig) for being so ahead of his time, yet now his music sounds fresher and more relevant than boring "preservationist" poseurs like Wynton Marsalis ever will. Ornette's work would be built upon by future saxmen--Albert Ayler, John Coltrane in his later years, Peter Brotzmann--all of whom would at some point emulate the unconventional ensemble and loose structure of Free Jazz and take it to even greater extremes.

Those guys will eventually make it to this column, by the way. But it all starts here.

Translation:

While it's probably not the best pick for a newbie to this genre, Free Jazz shouldn't intimidate anyone who has some affinity for '50s jazz. I would start out on some Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus and the aforementioned The Shape of Jazz To Come. Maybe a few Charlie Parker/Dizzy Gillespie recordings, too. This album is a little harder to get into than those, but compared to later free jazz releases this is downright pleasant. Just ignore Ken Burns and dive in.

-SJ

No comments:

Post a Comment